I’m sure most of you have experienced Low Back Pain (LBP) at some point during your life whether it be on or off the bike. It is estimated that the incidence of LBP is close to 50% in the general population alone. Low back pain is also one of the most common sites of pain in both professional and recreational cyclists. In one study low back pain (LBP) was reported to be responsible for up to 45% of all nontraumatic injuries in a group of 101 professional cyclists over a 1 year period of time. Epidemiological studies have also estimated that over 30% of recreational cyclists cite LBP as a common source of musculoskeletal pain during cycling as well. Low back pain can be caused by trauma (ie: crashing) but the focus of this article will be on nontraumatic sources of LBP in cycling.

Listed below are common causes of LBP in cyclists:

-

- Poor training principles

- Muscle weakness or core instability

- Inadequate mobility/flexibility

- Spinal conditions such as Degenerative Disk Disease, Osteoarthritis or Disk herniation

- Sacroiliac joint pain/dysfunction

- Anatomical variants such as leg length discrepancies or pelvic obliquity

- Postural abnormalities (excessive kyphosis, lordosis, scoliosis)

- Poor bike fit/equipment issues

It is fairly well accepted that a large contributing factor to LBP in cyclists is due to the prolonged forward flexed posture required when riding a bike. Some of us ride for 45 minutes to an hour for a quick work out and others ride for days on end in events such as RAAM. Most of us are probably somewhere in between, but all cyclists subject their spine to prolonged postures. This bent over posture places strain on our muscles, joints, tendons, ligaments and our disks. Our body is an amazing structure that typically adapts well to stresses placed upon it if these stresses are gradually introduced. However, if we use poor training principles we expose ourselves to potential musculoskeletal injury.

Common training mistakes are:

-

-

- increasing mileage/intensity too quickly

- excessive hill training

- using big gears

- initiating training on a different bike with a more aggressive position ie: time trial bike without adequate build up in mileage

-

In cycling and orthopedics the 10% rule is generally a safe way to progress time and or mileage while allowing your tissue to adapt to the new stresses placed upon them. For example; if you are cycling 100 miles per week, a safe increase in mileage would be 110 miles the following week. This is particularly true if coming back from injury. Obviously this is a guideline but in my practice I find it to be a very safe and effective way to increase training.

We all know that our core is important to protect the spine in everyday life and during cycling this is also the case. Poor endurance, core instability or muscular weakness in our hips, spine and abdominals can also be a source of LBP when on the bike. Although we do have our hands for support on the handlebars it is speculated that the core, particularly the spinal extensors are important postural stabilizers keeping us upright on the bike. When these muscles fatigue we are susceptible to increased and unwanted low back movement which can lead to pain and decreased performance. Studies have shown that our posture on the bike changes most notably at an effort above 60% of our VO2 max. So in essence our posture is not only affected by time on the bike but can also be affected by the intensity at which we ride as well.

We have all witnessed the fatigued struggling rider at the top of a climb who is all over his/her bike and cannot maintain a steady posture. Gradually building up our training is the best way to allow our body to adapt and improve our cycling specific strength and endurance. However, there are many exercises off of the bike that can also improve our core stability. We all know that there are a million ways to strengthen our core whether it be with bands, balls, weights, Yoga, Pilates, TRX, etc.. and all of these systems have merit and can be great ways to improve core stability. I have chosen to present several exercises below that are low back specific, equipment free (almost) and can easily be done at home and will improve lumbar/core stability both on and off the bike.

Specific exercise instructions for working on core stability can be found by clicking here (this is a pdf file).

Pictures:

1. Forward Plank

2. Side Plank Progression; 2A on knees, 2B on feet

3. Prone Scapular Retraction With Trunk Lift

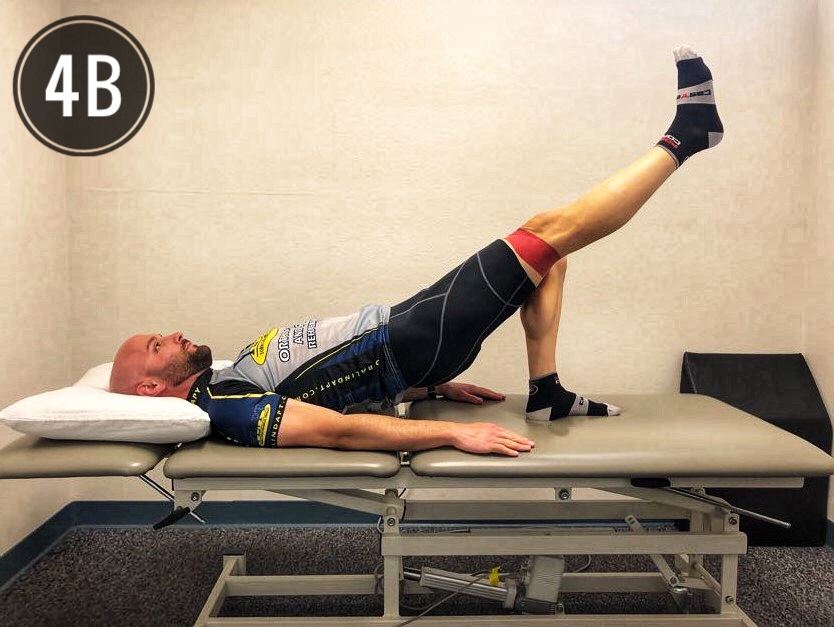

4. Bridging Progression; 4A intermediate, 4B advanced

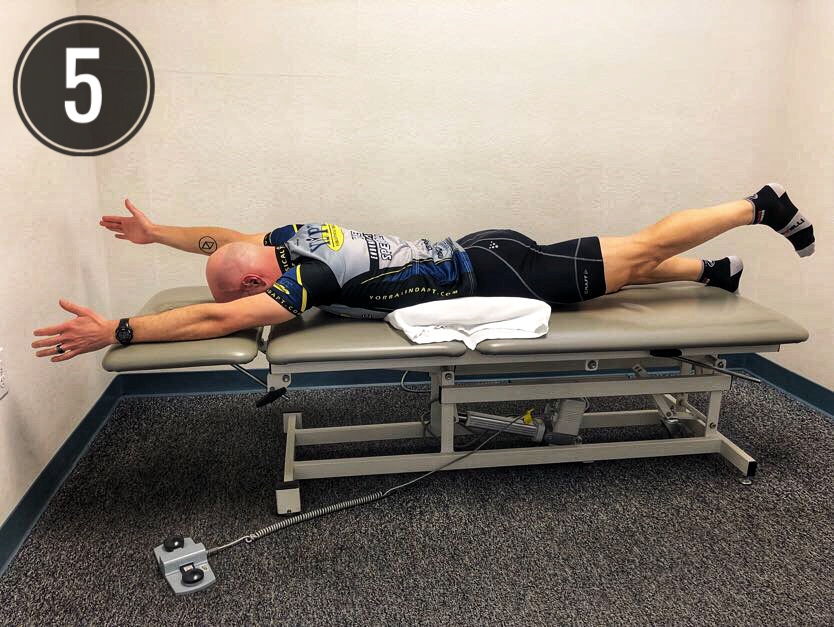

5. Prone Opposite Arm/Leg Extension

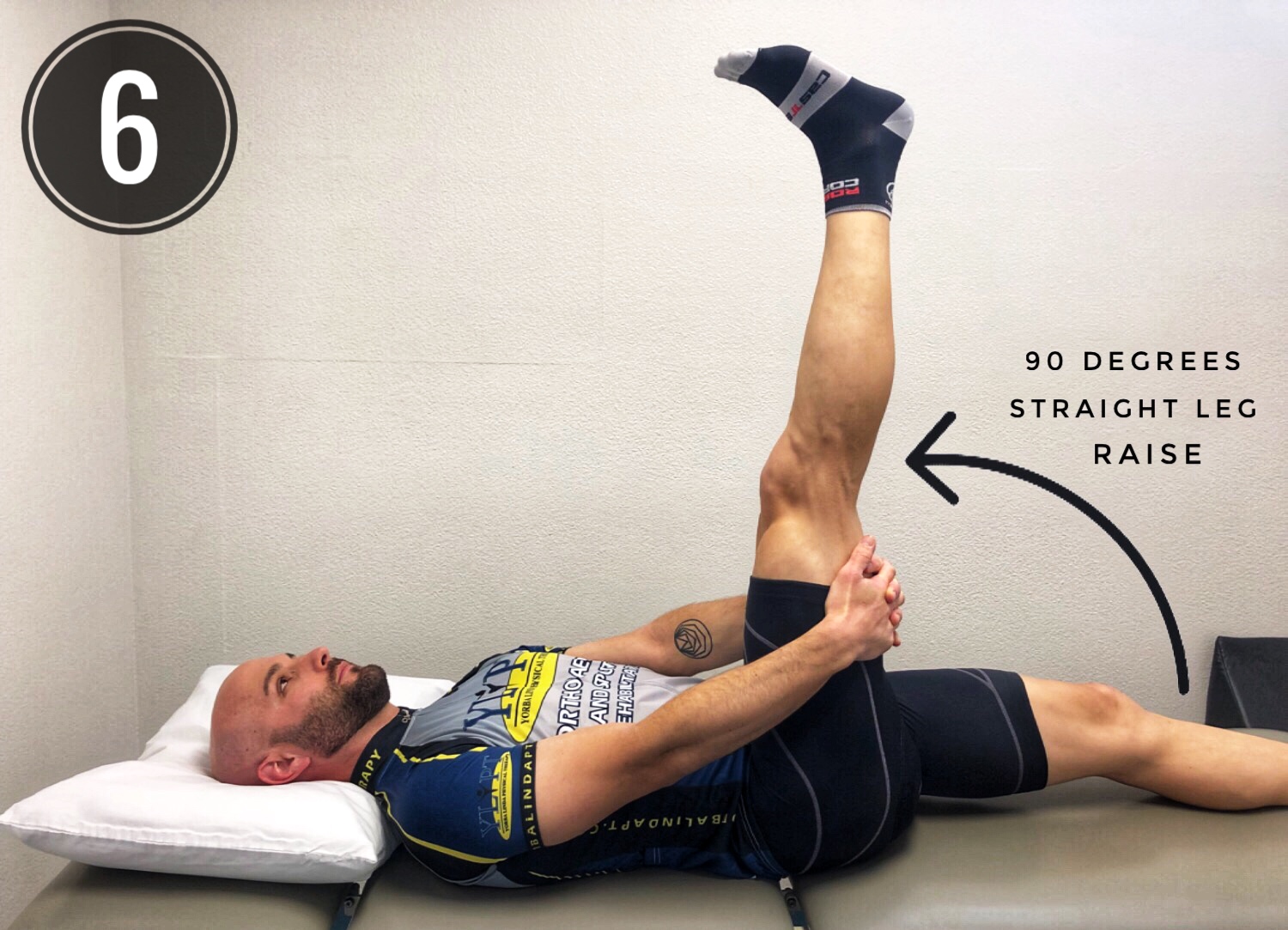

6. Straight Leg Raise, ideally 90 degrees or more

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Flexibility, or more commonly, lack of flexibility, is also a concern for cyclists given the prolonged demands of the sport. As mentioned above the forward flexed posture places our soft tissues including our disks on stretch and when sustained can cause pain and eventually tissue damage. Even the most limber riders still flex (round) their low back when cycling but those who have particularly tight hip extensors (glutes and hamstrings) are subjected to even more strain on the lumbar spine. Having adequate hip flexion of about 115 degrees and a straight leg raise of 90 degrees is desirable (see picture 6 above). These numbers may even need to be greater with the Aero position in time trialing. Also because cyclists are always flexed at the hips and recruit the hip flexors repeatedly during the back/upstroke this can lead to adaptive shortening of the hip flexors/IT Band which can cause low back, knee and hip problems off of the bike as well.

By no means is this an exhaustive list of all of the problematic areas of tightness in the body but the above mentioned areas are of the greatest concern in regard to the demands of the cyclist as it relates to the lumbar spine. Below I have included several important stretching exercises targeting the most problematic regions plaguing the cyclist.

Specific exercise instructions for working on flexibility can be found by clicking here (this is a pdf file).

Pictures:

7. Hamstring Stretch; 7A seated, 7B doorway

8. Single Knee To Chest

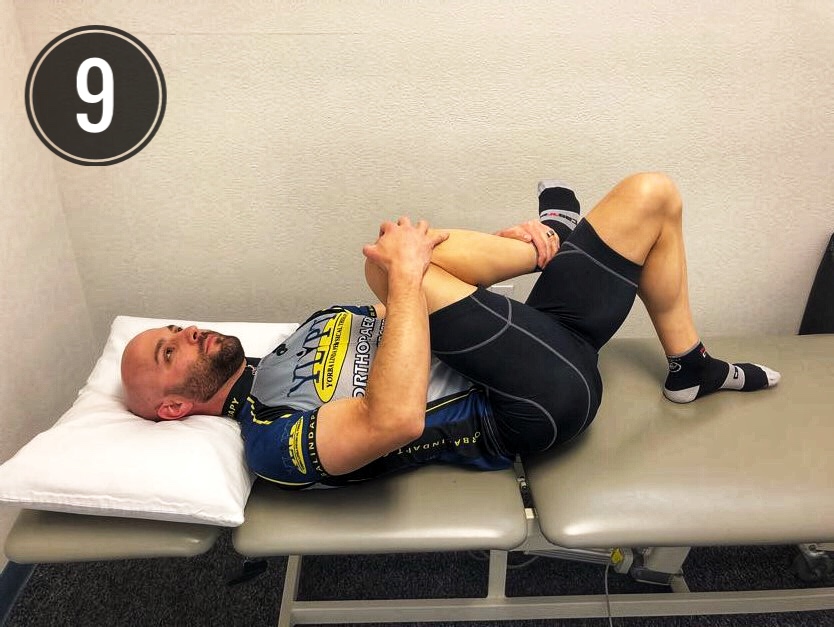

9. Piriformis Stretch

10. Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch

11. Open Book Stretch for Mid Back

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because of the repetitive nature of cycling and the prolonged postures assumed even small anatomical variants can become problematic for some over time. Some of these variants may include leg length discrepancies, genu varum (bow legs), genu valgum (knock knees), pes planus/overpronation (flat feet), increased spinal curvatures such as scoliosis, excessive kyphosis (hunch back), excessive lordosis (sway back) to name a few. There are also medical conditions that can predispose a rider to problems on the bike such as osteoarthritis, disk herniation/degeneration and stenosis.

Fortunately there a multitude of solutions available to accommodate many of these anatomical variants which may include shoe inserts, shims, wedging, pedal spacers, crank adaptors/length changes, a variety of saddle/bar choices as well as various pedal/cleat systems. The bike industry is continually evolving and now more than ever before there are many options available to adjust to our “imperfections”.

All of the topics discussed previously have more to do with conditions involving the cyclist or the cyclists’ training principles. However, often times the rider is healthy and training appropriately and they still have pain. Typically this is a result of an equipment issue or a poor bike fit.

There are numerous issues with regard to equipment/fit that can contribute to LBP. There can be issues with the saddle or the cleat position/pedal system that contribute to low back issues. However, the most common problem as it relates to the low back is the reach to the handlebars. Typically, a rider assumes too aggressive of a position. This long and low position places excessive strain on the spine. This can be a result of a long top tube or stem or a low bar position due to a short head tube or stem with insufficient rise. The bars can also have excessive reach, be too wide, rotated downward or the hoods can be rotated too low on the bar. Also riding habits can contribute to increased/low reach such as spending too much time in the drops.

The long and low riding position is not the only position responsible for low back pain but it is the most common. Conversely, there are times when the cockpit is too cramped which can lead to excessive strain on the spine as well. This can be from a seat positioned too far forward, a handlebar/lever combination with short reach, a frame with a short top tube or stem with inadequate length.

It is important to remember that even with an optimal bike fit postural breaks are important. Fortunately road bike handlebars have many options for hand placement so changing positions frequently is a good way to achieve a relative posture break while on the bike. This is particularly true if you are racing and cannot get off the bike. If you are not racing and you are on a long sustained climb the best posture break is to get off of the bike periodically, walk around to give your spine a break and enjoy the scenery!

Although adjustments in regard to bike fit can be made to alleviate some low back conditions it should be part of an overall comprehensive bike fit considering the size, stature and needs of the cyclist. An appropriate sized frame is a critical starting point. There are many really good local bike shops with qualified fitters that can assist with purchasing the right frame size, components and style of bike to meet the needs and goals of the individual cyclist. If you already have a bike they also can retrofit you to your bike and suggest changes to improve performance and or comfort.

If all training errors are avoided, a good bike fit has been achieved and pain persists then examination by a qualified licensed medical practitioner should be sought. This is especially the case if leg pain, numbness, tingling or changes in bowel/bladder control are present. Once serious conditions are ruled out, seeking advice from a provider with an extensive background in cycling, biomechanics and anatomy is likely the best means of resolving the problem. There is almost always a way to keep cycling pain free!

Rob Ortmayer, MPT, CSCS

Licensed Physical Therapist

Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist

Certified Level 2 USA Cycling Coach

Yorba Linda Physical Therapy